Written by: Kelly McKinnon

Illustration by: Kelly McKinnon

She’s innovative. She’s three-dimensional. She’s made out of human cells. She has a functional reproductive tract that includes an ovary, fallopian tube, uterus and cervix. She also has a liver, and the channels necessary to pump nutrients between her organs. She produces and responds to hormones, and has a normal 28-day hormone cycle. She can metabolize drugs. She can tell you how a drug may affect fertility in women, or if it is toxic to the liver. And she fits in the palm of your hand. She’s the future of drug testing in women and personalized medicine, and her name is Evatar. Just as Eve is thought to be the mother of all humans, Evatar is the mother of all microHumans.

Why is Evatar needed?

Evatar fills a gap in drug and toxicology studies by enabling testing of female tissue function in the presence of cycling hormones. Historically, females (human, animals and cells) have been neglected in drug studies for a number of reasons. In studies that use animals, researchers worry that female animals' fluctuating hormones may confound experimental results. Since male hormones don’t fluctuate as much, they stick to using male animals. Human clinical studies typically include only post-menopausal women. That’s because researchers worry about what impact potential drugs would have on a woman or her unborn child if she became pregnant during the study. So, whether the model is animal or human, the effects that drugs might have on women’s overall health (from cardiovascular health to Ambien doses) are not adequately evaluated. Evatar promises to fill this gap.

Additionally, since Evatar's organs are mostly made from human cells, we will be able to make personalized models for each patient in the future. If a patient, for example, is diagnosed with uterine cancer, we could use her own cells to make a model of her specific cancer, in order to test drugs that would work for her.

How does Evatar work?

Evatar contains small 3D organ models of the liver, and of each of the organs of the female reproductive tract: the ovary, which produces hormones, and the fallopian tubes, uterus and cervix, which respond to hormones. The liver, while not part of the reproductive tract, plays a major role in the metabolism of ovarian hormones, as well as external drugs. Each of these organs has a critical role in fertility and women’s health. We engineer these models using human cells obtained from women undergoing hysterectomies, cells that otherwise would be disposed of as medical waste.

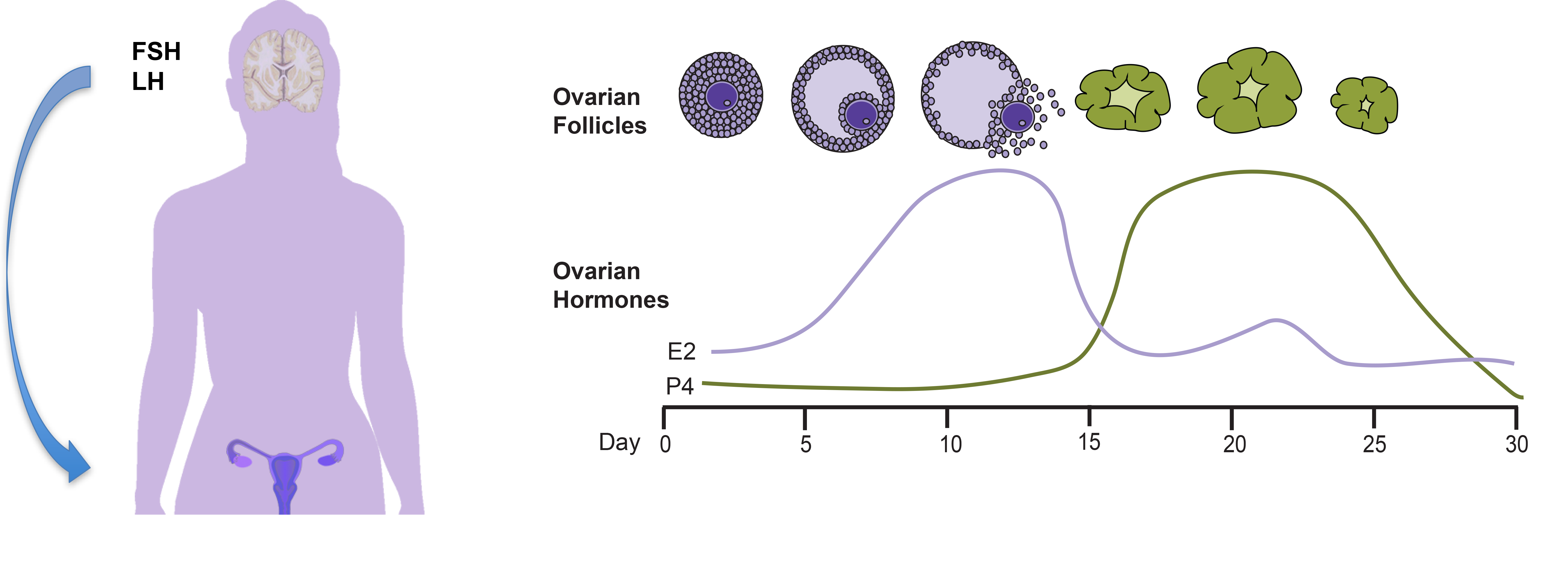

Evatar’s 3D reproductive tract organs and liver are all connected to each other in a layered platform: the top layer contains her organs, and the bottom layers contain the mini-pumps and channels that carry nutrients through the organs, and are programmable through a computer interface. Similar to the normal female menstrual cycle, Evatar’s ovaries produce cycling levels of hormones, and her pumps and channels carry these hormones to her other organs, which then respond in an observable and quantifiable way. When a potential drug disrupts her hormone production or response, she lets us know through specific measurable outcomes.

In the future, we will connect even more organs to Evatar, making it possible to give her a heart, lungs, and other vital organs. This will allow the study of interactions between organ systems, and the human body as a whole. Maybe one day Evatar will even become a new standard for pre-clinical testing of drugs. Of course, in this case, we will have to give her a partner in crime…HEvatar. Stay tuned.

![]()